Meds that DO NOT cross placenta: “He Is Going Nowhere”

Heparin, Insilun, Glycopyrrolate, Neuromuscular blockers (ALL paralytics)

Review Articles:

Anaesthesia for non-obstetric surgery during pregnancy

Anesthetic Management of the Pregnant Patient: Part 1

Anesthetic Management of the Pregnant Patient: Part 2

Non-Obstetric Surgery During Pregnancy

Maternal and Fetal Acid-Base Chemistry: A Major Determinant of Perinatal Outcome

Episode 160: Non-OB Surgery in Pregnancy With Dave Berman

GA for Parturients in Non-obstetric Surgery

- Fent, prop, & sevo fine. Zofran, Reglan fine for PONV, 0.5 haldol ok as single rescue dose.

- Dexamethasone: some studies claim teratogenicity – possible link to cleft palates in early embryonic development (1st TM). Safe in later pregnancy as steroids/glucocorticoids are routinely given for fetal lung development in perterms (betamethasone).

- Full stomach after 12 weeks –> RSI.

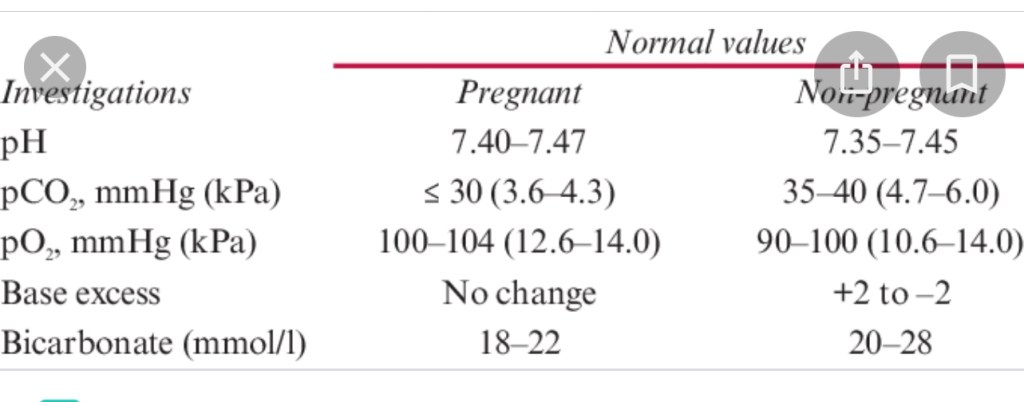

- Goal ETCO2 low normal: Mom has slight physiologic respiratory alkalosis 7.45.

- CO2 fall 2/2 progesterone being respiratory stimulant

- Lower maternal CO2 tension —> ^^transplacental gradient for fetus to off-gas CO2 and maintain delicate fetal pH balance

- No hypercarbia, no hypoxemia – any pH changes in mom —> more severe derangements in O2 delivery to fetus.

- No N2O in early pregnancy (possibly impairs DNA synthesis, possible link to miscarriages).

- No ketamine (uterotonic), no pre-term labor, possible fetal neuroapoptosis

- No Midazolam, (single dose probably ok, longer term benzo use assc w congenital cardiac anomalies)

- No Toradol* or NSAIDS (prostaglandins maintain patent ductus arteriosis in fetal circ. NSAIDs inhibit prostaglandins)

ALL NEUROMUSCULAR BLOCKERS FINE

BUT REVERSAL AGENTS…

Sugammadex is not recommended…(unless airway emergency)

- Glyco & Neostigmine preferred for reversal

- Atropine (0.1mg per 1mg of Neostigmine) ok too. But will cross placenta (while glyco & neostigmine don’t really cross) and may cause fetal tachycardia –> acidosis

- Glyco also fine to give for other maternal reasons: (eg: vagal reflex on insufflation, secretions, etc.)

- Sugammadex Controversial, but OK if emergency reversal needed

- Suggamadex binds progesterone (why contraceptives are less effective afterward)

- progesterone maintains a normal pregnancy, so it can reasonably be avoided in surgery for pregnant pts.

- Of course, in airway emergencies it’s still valuable.

- progesterone maintains a normal pregnancy, so it can reasonably be avoided in surgery for pregnant pts.

S.O.A.P Sugammadex POSITION 2019:

(Society for Obstetric Anesthesia & Perinatology)

AVOID Sugammadex in early pregnancy (until term)

SOAP sugammadex position statement excerpt: “ Pharmacological simulation studies by Merck (manufactures Sugammadex) indicate that a 4 mg/kg dose of Sugammadex is predicted to reduce unbound(active) progesterone levels by 34%, which is theoretically consequential given that progesterone secretion by the corpus luteum supports endometrial growth and is required for the success of early human pregnancy. Results from animal models are mixed: a single animal dose of Sugammadex 30 mg/kg, (max rec. human dose is 16 mg/kg) in early rat gestation did not affect the duration of pregnancy or rate of stillbirths or miscarriages.”

- So risk is theoretical but cannot ethically be tested on human fetuses.

Some case studies of Sugammadex being safe in pregnancy:

Good article on how Sugammadex & various antibiotics we give decrease contraceptive efficacy, and often isn’t discussed with patients enough in consent forms/post-op follow-up.

Sugammadex and Oral Contraceptives: Is It Time for a… : Anesthesia & Analgesia

HH Guidelines for Anesthesia for Non-Obstetric Surgery During Pregnancy (NOSDP)

Adam Sachs MD 2018 HH Clinical Practice Reference: CPR.02.490

No type of anesthetic (regional, general, TIVA, etc.) has been found to be superior over any other particular one with respect to maternal or fetal outcomes.

All common anesthesia medications, used in typical doses, are safe for the fetus. So far, there is no evidence that any of these medications increase negative fetal outcomes, including teratogenic or neurotoxic effects to the fetus.

Fetal Monitoring:

- Generally after a fetus is viable (23-24 weeks) continuous intra-op fetal monitoring and left uterine displacement of 15° should occur when feasible (the location, nature, and urgency of the procedure will dictate feasibility).

Steps to follow:

- Call 21955 and ask to talk to the “resource or charge nurse.”

- Helpful information to relay to the nurse other than the patients name and MRN include, the patients gestational age, patient’s obstetrician/OB group, what procedure will be occurring, the expected time the procedure will occur, and what the expected type of monitoring for the fetus is (pre and post op FHR or continuous fetal monitoring during the procedure).

- For planned/semi-elective procedures, the OB team/charge nurse should hopefully be aware of the patient, obstetrical clearance for the procedure (typically a written note) should have been obtained from the patient’s obstetrician, and a biophysical profile (BPP) or non-stress test (NST) should have occurred within 24 hours preceding surgery.

- If the above mentioned things have not occurred because the procedure is too urgent, at the minimum, a FHR should be obtained prior to the procedure, except in emergency procedures where this is not possible.

- The resource/charge nurse should help coordinate the care of the patient. This will

typically involve sending a labor and delivery nurse down to the operating room to monitor the fetus. - Please call labor and delivery as soon as you know you have a surgical case where the patient is pregnant because it will take some time to free up personnel to assist with the procedure (especially when continuous intra-op fetal monitoring is expected).

- Although typically a labor and delivery nurse will monitor the baby, the patient’s obstetrician, or at least a representative from the obstetricians group, should be notified and available in case an obstetrical intervention is necessary.

Background

Although multiple studies have shown non-obstetric surgery during pregnancy (NOSDP) to be safe for mother and fetus, alterations in maternal anatomy and physiology, induced by pregnancy, present clinical anesthetic implications and potential hazards.

- Maternal Problems:

- Increased incidence of difficult/failed intubation as compared to the general population

- Increased risk of hypoxemia on induction/emergence 2/2 physiologic changes of pregnancy (reduced FRC plus increased minute ventilation and O2 consumption)

- Increased risk of aspiration

- Increased incidence of CVA (esp in PreE)

- Fetal Problems:

- Risk of intra-op hypoxemia or asphyxia caused by reduced uterine blood flow, maternal HOTN, excessive maternal mechanical ventilation or maternal hypoxia, depression of the fetal cardiovascular system or CNS from placental passage of anesthetic agents.

- Exposure to possibly teratogenic drugs, specifically during the organogenesis stage (1st trimester).

- Risk of miscarriage or preterm delivery as a consequence of the surgical procedure, disease process, or drugs administered.

DNR

- It is the policy of Hartford Hospital and the medical Staff that orders not to resuscitate in the event of a cardiopulmonary arrest (“DNR orders”) be specifically reviewed as to their applicability during the procedural period. This includes any pregnant patient, with a DNR order, scheduled for surgery.

Preoperative Assessment

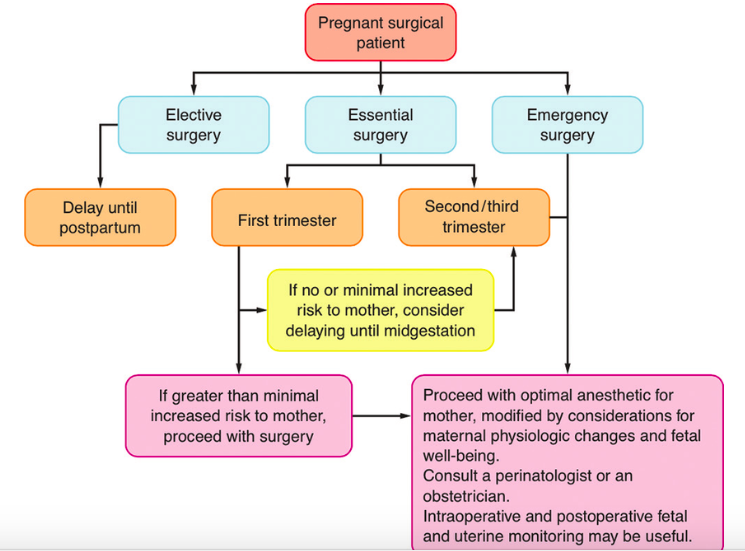

- Elective procedures (other than postpartum tubal ligation) should be deferred until after delivery (preferably 4-6 weeks postpartum)

- For semi-elective or non-elective surgery: An indicated surgery should not be denied because of pregnancy (regardless of trimester).

- An informed “team” discussion should occur regarding the risks/benefits of surgery and the optimal time to complete the surgery.

- Team members may include, but are not limited to:

- the surgeon performing the surgery, anesthesiologist/anesthesia team, obstetrician (preferably an obstetrician from the patient’s own group/familiar with the patient) and a neonatologist.

- Team members may include, but are not limited to:

General Guidelines

- 1st trimester – if no or minimal increased risk to the mother, consider delaying until the 2nd trimester; if risk to the mother, proceed with surgery.

- 2nd trimester (14-26wks) – “best” time for non-elective surgery, in order to avoid the 1st trimesters higher risk of miscarriage and organogenesis phase as well as the higher incidence of preterm labor associated with 3 rd trimester

- 3rd trimester – if no or minimal increased risk to the mother, consider delaying until after delivery; if risk to the mother, proceed with surgery.

- For emergency surgery, proceed with the optimal anesthetic for the mother, modified by considerations for maternal physiologic changes and fetal well being

Patient Counseling

- If a patient is undergoing a surgery during pregnancy, then it has hopefully already been established that this is a non-elective procedure that needs to be completed for maternal safety.

- Although the anesthesia team should adequately counsel the patient regarding the risks of anesthesia to the fetus/pregnancy, it should be done in a caring and sensitive manner to not exacerbate an already difficult and scary situation for the mother.

- The initial question for patients undergoing NOSDP is commonly, “what effects will the anesthesia have on my baby?” A helpful thing to keep in mind is that NO single modern anesthetic agent, used in typical doses, has been shown to cause birth defects (at any gestational age), neurotoxicity, or increase the risk of a negative pregnancy outcome. Furthermore, with regards to the fetus, the risk of not having surgery is typically greater than proceeding with surgery, especially when there is a risk of developing sepsis, peritonitis, or bacteremia.

- Although the above statement is accurate, NOSDP does cause an increased risk of miscarriage (most likely not related to the anesthetic) and a theoretical risk of teratogenicity/neurotoxicity (as discussed below). Deciding on how to council NOSDP patients regarding these issues is challenging and controversial since teratogenicity/neurotoxicity are theoretical concerns and the increased incidence of miscarriage appears to be secondary to the disease process and not the anesthetic (as discussed below).

- Based on the current data, it seems reasonable to reassure patients that no long term negative consequences have been shown to occur with anesthesia.

Data for Clinicians Regarding Teratogenicity , Neurotoxicity & Negative Pregnancy

Outcome

- Teratogenicity and Neurotoxicity:

- Laboratory and animal studies, including studies in non-human

primates, have reported neuronal apoptosis, changes in dendritic morphology, teratogenicity, and negative effects on neurodevelopment after anesthetic exposure for almost all anesthetics used in clinical practice.- These studies are problematic because they typically involve non-human subjects, exposer to doses 10-1000 times greater than what is clinically used, for excessive periods of time (days/weeks/months).

- With respect to human studies, no significant data exists regarding neurotoxicity of anesthetics on fetal brain development in utero, therefore the only available data comes from early childhood exposure studies.

- In young children, some observational studies have reported no association between early pediatric exposure to anesthesia and negative neurodevelopmental outcomes

whereas others have reported an increase in neurodevelopmental delay, learning disabilities, and

ADHD.

- In young children, some observational studies have reported no association between early pediatric exposure to anesthesia and negative neurodevelopmental outcomes

- The conflicting data that exists prompted the initiation of SmartTots, which is a collaborative effort of the IARS, the U.S. FDA, and other organizations, to investigate the safety of anesthetics on early childhood development. To date, the well conducted, high powered studies (GAS study, PANDA study, etc) have found no clinically significant effect on neurodevelopmental outcome, or IQ scores, for pediatric patients exposed to anesthesia in early childhood.

- Laboratory and animal studies, including studies in non-human

- Pregnancy Outcome:

- The available data shows an increased risk of negative pregnancy outcomes (most notably preterm labor, preterm delivery, IUGR, and miscarriage) when surgery occurs during pregnancy. This is especially high in patients with systemic disease (sepsis/peritonitis) and patients who already have risk factors for preterm delivery (incompetent cervix, previous preterm delivery, etc). Based on the limited data, there is currently no evidence that anesthesia increases the risk of negative outcomes and the increased fetal risk is probably related to the underlying disease process.

Individual Anesthetics

- The majority of anesthetics cross the placenta and will affect the newborn.

- exceptions include:

- Muscle relaxants (Succinylcholine, Rocuronium, etc.), Neostigmine, and possibly Glycopyrrolate.

- exceptions include:

Anesthetics with Long Records of Safety

- Inhalation agents:

- (Sevoflurane, Desflurane)

- IV induction agents

- (Propofol, Etomidate)

- Narcotics:

- (Fentanyl, Hyrdromorphone, Morphine)

- Muscle Relaxants:

- (Rocuronium, Succinylcholine)

- Local Anesthetics

Other Anesthetics & Their Considerations

- Benzodiazepines (pregnancy class D):

- Benzodiazepines may inhibit palate shelf reorientation leading to cleft palate. Human retrospective studies have shown an association between chronic diazepam use early in pregnancy and cleft palate. This association has not been shown in case-control and prospective studies however.

- If Midazolam is not needed for a procedure it may be better to avoid it, especially during the first trimester (organogenesis), however if the clinician thinks there is a medical necessity or purpose to its use then it should not be withheld.

- Nitrous Oxide

- Nitrous oxide oxidizes vitamin B12, which then cannot function as a cofactor for methionine synthetase and inhibits DNA synthesis.

- Nitrous oxide has not yet been found to be associated with congenital abnormalities in humans although it has in other mammals.

- Based on its mechanism of action and its pro-emetic potential it is probably best if avoided during pregnancy, especially during the first trimester, unless medically necessary.

- Ketamine

- Ketamine may cause a dose dependent increase in uterine contractions. Although it is ok to use ketamine, try to avoid in high doses (> 2mg/kg).

- Sugammadex

- There is limited data to establish fetal safety of Sugammadex when used in pregnant women. Sugammadex appears to cross the placenta whereas Neostigmine, and possibly Glycopyrrolate, do not.

- Neostigmine/Glycopyrrolate/Atropine

- Neostigmine and Glycopyrrolate are both quaternary ammonium compounds and theoretically should not cross the placenta.

- There are 2 case reports that discuss a decrease in fetal heart rate after reversal with Neostigmine/Glycopyrrolate which the authors thought may have been secondary to Neostigmine crossing the placenta.

- Neostigmine/Glycopyrrolate has a long record of safe use and can be used for reversal, especially if given slowly and in smaller doses (less than 5mg of Neostigmine).

- If you prefer, Atropine (0.1mg per 1mg of Neostigmine) can be used in place of Glycopyrrolate but this can cause fetal tachycardia and may result in fetal acidosis.

- NSAIDS

- Considered safe for use up until 30wks gestation.

- From week 30 onward, please avoid NSAIDS because of the risk of premature closure of the ductus arteriosus.

Preoperative Medications

- Preoperative anxiolytic medication may be appropriate, since elevated maternal catecholamines may decrease uterine blood flow.

- Narcotics (as well as benzodiazepines?) may be used with caution (pregnancy patients require smaller doses as they are more sensitive to the sedative and respiratory depressant effects of these medications, and they are considered to have a “full stomach” which poses an aspiration risk when these patients become obtunded).

- Consider aspiration prophylaxis:

- combination of nonparticulate antacid & metoclopramide and/or H2-receptor antagonist.

Tocolytic Agents

- Uterine tocolysis is not generally prescribed unless:

- uterine surgery is performed

- documented uterine irritability is identified

- or an intraperitoneal inflammatory process is diagnosed.

- Indomethacin and magnesium sulfate are both common tocolytics used. Indomethacin has few anesthetic implications, but magnesium sulfate can potentiate muscle relaxants and make HOTN more difficult to treat during blood loss or volume shifts.

Intraoperative Monitoring

- Standard ASA monitors for BP, oxygenation, ventilation, EKG and temperature.

- Blood glucose:

- Pts with stable BG levels don’t need an intra-op sample unless medically indicated.

- Keep in mind Blood glucose levels during pregnancy are lower (fasting blood glucose 60-90).

- Left uterine displacement to prevent aortocaval compression for any pregnant patient > 20 weeks gestation if feasible.

Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring:

The gestational age, maternal and fetal history, nature and urgency of surgery need to be considered. The decision to monitor fetal heart rate intra-operatively should be determined via consultation between the anesthesia team, obstetrician, surgeon and in certain circumstances neonatologist.

Elective

- Prior to 9 weeks gestation:

- No pre, intra or post-op fetal evaluation.

- 9 weeks to viability

- What is considered viable is constantly changing, but currently around 23 wks gestation

- Pre-op & Post-op FHR check by Doppler or ultrasound by OBGYN or L&D RN, recorded on chart.

- Viability/23 weeks gestation until delivery:

- According to ACOG (American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists), continuous intra-op FHR monitoring should be considered when:

- The fetus is considered viable/likely to survive

- It is physically possible to perform/it will not interfere with the surgical field (not possible during a laparoscopic appendectomy)

- An obstetrician is available and willing to intervene during the procedure

- When possible, the patient should give informed consent for an emergency C/S delivery.

- The surgery can safely be interrupted to allow for emergency delivery (ie: stopping crani for a tumor resection with the patients head in pins to attempt to deliver a fetus is probably not safe).

- According to ACOG (American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists), continuous intra-op FHR monitoring should be considered when:

- In addition, to the criteria above, some people believe that intra-op monitoring should be extended to pre-viable fetuses, and viable fetuses without a delivery plan, as “another vital sign” or a way to assure the intrauterine environment is “optimized.” The idea being that if fetal bradycardia occurs during induced hypotension, cardiopulmonary bypass, volume shifts/blood loss, induction of anesthesia, etc., the anesthesia personnel can take corrective measures to alleviate the fetal bradycardia (more left uterine displacement, increase blood pressure, higher FIO2, etc.).

- While this seems beneficial on the surface there are lots of problems as well:

- General anesthesia can cause decreased variability and a lower baseline fetal heart rate so interpretation can be inaccurate

- Continuous fetal monitoring prior to 26 weeks may not be possible because of normal fetal activity/movement (due to small size of fetus/not engaged in pelvis).

- Anesthesia related interventions to improve utero-placental perfusion are limited under general anesthesia (other than making sure the patient is positioned with left uterine displacement and maternal blood pressure, heart rate, O2 Sat and ETCO2 are in a normal physiologic range there isn’t anything anesthesia personnel can do).

- Increased coordination of care/necessary personnel results in delays in maternal care which could cause harm to the fetus.

- While this seems beneficial on the surface there are lots of problems as well:

- While there is nothing wrong with continuous intra-op FHR monitoring in these additional cases, we currently only require continuous intra-op FHR monitoring as defined by the ACOG guidelines listed above.

Pre-op steps to follow if a pt is undergoing NOBSDP with a viable fetus:

- Call 21955 and ask to talk to the “resource or charge nurse.”

- Helpful information to relay to the nurse other than the patients name and MRN includes : the patients gestational age, patient’s obstetrician/OB group, what

procedure will be occurring, the expected time the procedure will occur, and what

the expected type of monitoring for the fetus is (pre and post op FHR or continuous

fetal monitoring during the procedure). - For planned/semi-elective procedures, the OB team/charge nurse should hopefully

be aware of the patient, obstetrical clearance for the procedure (typically a written note) should have been obtained from the patient’s obstetrician and a biophysical profile (BPP) or non-stress test (NST) should have occurred within 24 hours preceding surgery. - If the above mentioned things have not occurred because the procedure is too

urgent, at the minimum, a FHR should be obtained prior to the procedure, except in

emergency procedures where this is not possible. - The resource/charge nurse should help coordinate the care of the patient. This will

typically involve sending a labor and delivery nurse down to the operating room to

monitor the fetus. - Please call labor and delivery as soon as you know you have a case where the

patient is pregnant because it will take some time to free up personnel to assist

with the procedure (especially when continuous intra-op fetal monitoring is

expected). - Although typically a labor and delivery nurse will monitor the baby, the patient’s

obstetrician, or at least a representative from the obstetricians group, should be

notified and available in case an obstetrical intervention is necessary. - Intra-op steps to follow if a patient is undergoing NOSDP with a viable fetus/over 23 weeks gestation:

- Try to maintain maternal vital signs close to preoperative/baseline vital signs (BP generally maintained greater than 90/50, O2 SAT >95%,

- Left uterine displacement of at least 15 degrees when feasible

- Loss of beat-beat variability and decreased baseline fetal heart rate are normal under anesthesia, severe, especially when prolonged, FHR decelerations are not normal.

- Suggested interventions for intra-operative fetal distress:

- Increase maternal FiO2

- Increase maternal BP

- Increase left uterine displacement (or try right uterine displacement)

- Move retractors or discontinue uterine/abdominal pressure

- Administer tocolytic if patient is having frequent contractions

- Document your interventions

- Post-op steps to follow if a patient is undergoing NOSDP with a viable fetus/over 23 weeks gestation:

- Assessment of FHR and uterine contractions for 20 minutes by trained personnel (usually labor and delivery nurse)

- If FHR is unstable (less than 110bpm or greater than 160bpm), or active contractions are present, the patients OB team/obstetrician should be notified and continuous external fetal monitoring (EFM) is most likely indicated for a prolonged period of time.

GA: When are pregnant women considered “full stomachs?”

- There is substantial data that shows that pregnant women, especially when full term, are at an increased risk of aspiration with anesthesia but unfortunately there is limited data regarding at what gestational age this becomes clinically relevant.

- It is believed the increased risk is multifactorial arising from progesterone-induced relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter and cephalad displacement of the stomach from the enlarging uterus.

- Progesterone levels drastically increase during the first trimester, sometimes almost reaching peak levels by the start of the second trimester.

- It had been largely believed that pregnant women should be considered full stomachs as early as the 12th week of pregnancy.

- Additional studies have revealed that this school of thought was likely overly cautious.

- In 2011, a study published in the Journal of Clinical Anesthesia looked at data from an outpatient abortion clinic that did all of their cases under propofol deep sedation. In this retrospective review, there were over 62,000 cases performed without any cases of pulmonary aspiration, despite 11,000 second trimester cases with 2600 between 19 and 23 weeks gestation and 365 cases between 23 and 24 weeks.

- Additional studies have revealed that this school of thought was likely overly cautious.

- Based on the current literature it is reasonable to consider pregnant women “full

stomachs” after 18 weeks gestation if they don’t have any risk factors for aspiration. - Pregnant women with morbid obesity, severe GERD, uncontrolled diabetes, hiatal hernia, gastroparesis/gastric emptying disorder, actively nauseous/vomiting, or any other condition which increases aspiration risk should probably be considered a full stomach regardless of gestational age.

- There is no evidence that any anesthetic technique is better as long as maternal oxygenation and uterine perfusion are maintained.

Special Situations

- Trauma

- #1 cause of maternal death

- fetal loss usually due to maternal death or placental abruption

- need early ultrasound in ER to determine fetal viability; perform all needed diagnostic tests to optimize maternal management (shield the fetus when possible).

- #1 cause of maternal death

Indications for Emergent Cesarian Section

- Stable mother and viable fetus in distress

- Traumatic uterine rupture

- Gravid uterus interfering with intra-abdominal repairs

- Maternal CPR (need to improve venous return)

- Mother who is unsalvageable with viable fetus

Neurosurgery

- Induced hypotension:

- (aneurysm, AVM) decreases uterine perfusion

- All agents: NTP, NTG, hydralazine, esmolol, inhalation agents – have been used successfully during pregnancy.

- FHR monitoring helps determine if uterine perfusion is impaired, but still need to do what is necessary for optimal care of the mother.

- Hyperventiliation

- Reduces maternal cardiac output and decreases O2 release to fetus by shifting the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve to the left.

- Need fetal shielding during endovascular treatment of acutely ruptured intracranial aneurysm.

- Diuresis with osmotic agents(mannitol) can cause significant negative fluid shifts for the fetus.

Cardiac Surgery Requiring Cardiopulmonary Bypass

- Increases in blood volume and cardiac output significantly increase at 28-30 weeks gestation, so this is a high-risk time for cardiac decompensation in patients with cardiac lesions; also at risk immediately postpartum with release of aortocaval compression and autotransfusion of uteroplacental blood.

- Optimal flows and pressures on CPB are unknown (recommend maintaining pump flows 30%-50% greater than usual).

- FHR monitoring can be used to optimize flows. Fetal bradycardia occurs at the onset of CPB, and then slowly returns to a low baseline, with poor or no beat-to-beat variability.

- Avoid high-dose vasopressors if possible because of their effect on uterine blood flow; maintain MAP @ 60mmHg.

- Optimize acid-base status.

Laparoscopic Procedures

- CO2 pneumoperitoneum does not cause fetal hemodynamic changes, but it does induce a fetal respiratory acidosis

- normalizing maternal EtCO2

- produces late and incomplete correction in the fetus.

- Maintain intra-abdominal pressure as low as possible (8-12mmHg, do not exceed 15mmHg)

- Keep operative time (and insufflation time) to a minimum.

- Pneumoperiotoneum and enlarged uterus further limit diaphragm expansion, leading to decreases in BP, reduced FRC, increased V/Q mismatch, reduced thoracic cavity compliance, and increased pleural pressure.

- Keep operative time (and insufflation time) to a minimum.

- Advantages of laparoscopy vs. open procedures include:

- less negative fetal outcomes

- less postoperative pain and ileus

- shorter hospital stay

- more rapid ambulation

- better respiratory function

- reduced narcotic requirement and opioid-related respiratory depression

- fewer wound complications.

References:

- Anesthesia for the Pregnant Patient Undergoing Nonobstetric Surgery. Hawkins, Joy L., ASA Refresher Courses in Anesthesiology, 33 (1): 137-144, 2005.

- Nonobstetric Surgery During Pregnancy: What Are the Risks of Anesthesia? Kuczkowski, K.,

- Obstetrical and Gynecologic Survery, 2003 59 (1): 52-56.

- Anesthesia for Surgery During Pregnancy. Datta, S., Obstetric Anesthesia Handbook, 4 th Edition, 2006.

- Nonobstetric Surgery in Pregnancy, ACOG Committee Opinion Number 284, August 2003.

- Management of Anesthesia for the Pregnant Surgical Patient. Rosen, Mark A. Anesthesiology 91 (4), Oct. 1999: 1159-1163.

- Severe Fetal Bradycardia in a Pregnant Surgical Patient Despite Normal Oxygenation and Blood Pressure. Ong, Bill Y., et al, Can J Anesth 2003 50 (9): 922-925.

- Unnecessary Emergency Caesarian Section Due to Silent CTG During Anesthesia? Immer-Bansi, A., et al, British Journal of Anaesthesia 2001: 87 (8), 791-793.

SOAP & Open Anesthesia Fellow Webinar Series:

Trauma in Pregnancy: October 2022

Lecture quick notes:

- Consult OB on all cases

- Higher rates of hepatic & splenic lacerations 2/2 increased vascularity

- Higher risk of death in pregnant women 2/2 severity of injuries, bleeding risk, physiological changes of pregnancy.

- Blunt trauma is highest cause of traumatic maternal death.

- Retroperitoneal bleed more common in 3rd TM in setting of vascular engorgement

- Increased rates of bladder rupture 2/2 bladder displacement in pregnancy

- GSW: 19% risk visceral injury pregnant vs. 83% non-pregnant – Uterus shields abdomen.

- Also risk of ABRUPTION 2/2 direct trauma and deceleration /shearing force injuries. (eg: MVC with seatbelt and whiplash)

- Abruption: from whiplash/shearing MVC injury: can cause massive hemorrhage

- AFE also possible in 2nd&3rd TM trauma -can be caused from same mechanism as abruption with uteropacental interface trauma

- Hypovolemia and hemorrhagic shock main causes of codes in pregnancy.

- If > 24 wks, Left uterine displacement appropriate

- May need stat c/s for maternal recuscitation

- if fetus/gravid uterus big enough to cause aortocaval compression and compromise maternal circulation

- > 20-24 wks OR if uterus can be palpated at umbilicus.

- Autotransfusion after delivery significantly increases maternal intravascular volume & preload (~700cc) (= benefit of rapid fetal delivery)

- Perimortem c/s IS PRIMARILY TO IMPROVE MATERNAL OUTCOMES.

- Autotransfusion after delivery significantly increases maternal intravascular volume & preload (~700cc) (= benefit of rapid fetal delivery)

- Uterine rupture < 1% gravid traumas

- Grave fetal and maternal outcomes.

- Risk increases with maternal age.

- Maternal death rates up to 40% & fetal out-of-hospital death rates up to 90%

- IMAGING:

- Avoid MRI in 1st TM if possible (organogenesis)

- Ultrasound & MRI preferred, BUT: CT, nuclear med, and X-ray, if needed, should NOT be withheld. Exposure is well below exposure assc w/ fetal harm.

“THE FETUS TOLERATES MATERNAL DEATH POORLY”

- All CPR guidelines the same – same doses for maternal ACLS

- Remove FHR monitor before delivering shock – theoretical risk of electrical burns.

Link to Trauma in Pregnancy Webinar: October 2022:

AFE

- AFE can be another possible cause of LOC/CV collapse, especially in abdominal trauma. Can be superimposed on other injuries/pathologies:

- AOK therapy: Inappropriate in the trauma patient since Ketorolac can worsen major internal/intracranial bleeding.

- There is no way to definitively determine or test for +AFE which could be superimposed on other reasons for LOC/CV collapse: hemorrhagic shock/neurogenic shock/tamponade/aortic dissection, etc.

- High airway pressures & RV failure 2/2 bronchospasm, pulmonary vasospasm, and RV strain on TTE/POCUS may be seen in AFE, (RV strain could also be seen in PE). No clear diagnostic indicators or tests have been established as diagnostic for AFE, and it is ruled out by exclusion.

- High risk of DIC, especially with concurrent trauma –> TEG/ROTEM & coags/fibrinogen

BLOOD PRODUCTS

O-negative, CMV-negative blood, consider Rh immunotherapy if possibility of uterine injury.